Neonatal Diarrhoea

Importance and economical relevance of neonatal diarrhea

Neonatal diarrhea is one of the most common diseases on pig farms today. In recent years, pig production has changed and become increasingly intensified. Consequently, the number of animals on the farm is increasing, with associated changes in management. The intensive farming contributed to the increase in occurrence of neonatal diarrhea, which causes significant economic losses and excessive use of antimicrobials in the farrowing barn.

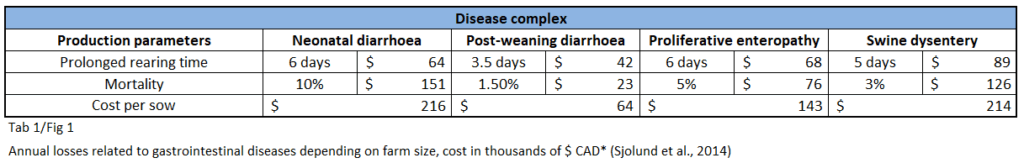

Estimated costs for herds affected by neonatal diarrhea with mortality of 10 % caused by disease can be as high as 134 Euro (equivalent to 216 $CAD*) per sow per year. Together with Swine dysentery, neonatal diarrhea is the most expensive enteric issue on pig farms (tab. 1 and fig. 1) (Sjolund et al., 2014).

The frequency of neonatal diarrhea cases has increased in the EU in recent years, affecting farms with conventional herd health status as well as well-maintained farms with good management practices.

* Conversion euro to $ CAD, August 11th, 2025

A 2024 study sampled 54 Canadian farms (Ontario, Quebec, and Western provinces) with neonatal diarrhea cases: 84.9% of farms tested positive for Clostridioides difficile A toxin, 100% of farms tested positive for Clostridium perfringens type A (CPA) α-toxin, 32% of fecal samples showed co-infection with both C. difficile toxins A and B, Rotavirus A was found in 78.9% of tested farms, and Rotavirus C in 52.6% (DeGroot et al., 2024).

Pathogens of the neonatal diarrhoea complex

Neonatal piglet diarrhea is a very common and significant problem in modern pig production. It is associated with increased pre-weaning mortality, poor growth rates, and weight variation at weaning. The newborn piglet has an immature mucosal immune system at birth, making it susceptible to early colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by pathogens.

By definition, neonatal diarrhea is characterized by diarrhea that develops during the first week of the piglet ‘s life (usually within the first few days after birth).

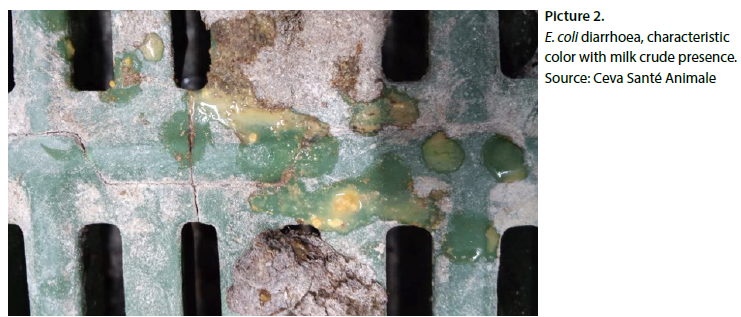

Escherichia coli complex

Among bacterial infections, Escherichia coli (E. coli) has historically been considered one of the main agents causing neonatal diarrhea in pigs (Chan et al., 2013). Different E. coli pathotypes have been identified based on their toxin production and other virulence factors. The most common are enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) strains, characterized by the production of enterotoxins (STa, STb and LT) and different fimbriae (adhesins). Both the toxins and fimbriae are considered virulent factors.

Other pathotypes of E. coli have been detected in piglets, such as enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strains that produce intimin (encoded by the eae gene), have also been identified in piglets. However, these are less common, and their practical significance is relatively low. (Toledo et al., 2012).

ETEC strains responsible for neonatal diarrhea possess adhesins — surface proteins called fimbriae — identified as F4 (k88), F5 (k99), F6 (987P) and F41. These fimbriae allow the microorganism to adhere to specific receptors located on the brush borders of the small intestines’ enterocytes.

The most prevalent ETEC with fimbriae F4 colonizes the length of jejunum and ileum, while those with fimbriae F5, F6, and F41 primarlycolonize the posterior jejunum and ileum. Susceptibility to ETEC F5, F6 and F41 decreases with age and is linked to a reduction in the number of active receptors present on the intestinal epithelial cells. Most ETEC strains of neonatal colibacillosis produce heat stable enterotoxin STa, which binds to the guanylyl cyclase C glycoprotein receptor on the brush border of villous and crypt intestinal epithelial cells, stimulating the production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). The resulting increase of cGMP causes electrolyte and fluid secretion, leading to watery diarrhea if the excess fluid from the small intestine is not absorbed in the large intestine. Excessive secretion leads to dehydration, metabolic acidosis, and eventually, death (Diseases of Swine, 10th edition).

Clostridium complex

Anaerobic bacterial pathogens such as enterotoxigenic strains of Clostridium perfringens type A (CpA) (producing Cpα toxin, β2 toxin), C. perfringens type C ( Cpβ toxins) are important pathogens in the complex of neonatal diarrhea and diarrhea before weaning (Uzal and Songer, 2019). Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) which produces enterotoxin A (TcdA) and/or cytotoxin B (TcdB), can also be isolated and cause similar disease to CpA. Clostridia are large, sporulating, gram-positive rods. Pathogenic strains produce one or more toxins with either direct or indirect roles in the pathogenesis ofneonatal diarrhea. A widely used system of classification of C. perfringens is based on presence of Major toxins genes and production of toxins: α, β, ε, τ, θ. From a swine medicine perspective, CpA and CpC are the most dominant pathogens, causing infection in piglets.

Clostridium perfringens type C

CpC is a primary pathogen of piglets. Organisms persist in the environment and are resistant to heat, disinfectants, and UV radiation. Multiplication of CpC in affected piglets — following infection from mother or from contaminated environment — leads to hemorrhagic necrotic enteritis, characterized by bloody diarrhea, accompanied by high mortality. The case fatality is up to 100 %. Infection can be as early as 12 h after birth, usually within the first 7 days of age (DOA). Sows are the source of infection for piglets. Newborns acquire passive immunity by absorption of undigested immunoglobulins (antibodies) from colostrum during the first 24-36 h after onset of colostrum ingestion. Colostrum trypsin inhibitors were suggested to be of possible pathogenetic significance in enteritis in newborns. The β-toxin of CpC is inactivated by trypsin and could easily be protected by the trypsin inhibitor in sow colostrum (P.T. Jensen, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00900993, 1978).

Infection occurs epidemically on farms where effective vaccination is not applied. Hallmark lesions are profound, usually segmental, mucosal necrosis with marked hemorrhage and emphysema of small intestine, principally the beta1 toxin acts systemically as well.

Clostridium perfringens type A

CpA is a normal inhabitant of the swine intestinal microbiota, but certain strains with the appropriate virulence factors can cause enteric disease. Infection of piglets is characterized by mild inflammation of the mucosa, occasionally with adherent necrotic material. Microscopic lesions may include superficial epithelial damage, particularly at the tips of the villi, and are usually localized in the jejunum and Ileum.

Macroscopic changes of intestinal mucosa might be subtle and discrete, requiring a microscopic assessment. Diarrheic cases usually correspond with P-A affection of intestine and presence of large numbers of pathogenic bacteria associated with the lesions.

Principal toxin type is alpha toxin, often accompanied by β2 toxin (CPB2; cpb2 is the encoding gene, Jost et al., 2005). Mucosal adherence plays a key role in toxin production. Clinical signs have been reproduced experimentally (Johannsen et al., 1993).

CpA infections are typical during the first days (one week) of the life of the piglets, and the sow is usually the source. CpA is also a very early colonizer of newborn piglets. The presence of CPB2-positivity CpA strains (dectected by PCR) helps differentiate between normal flora and pathogenic type A strains. Clinically, diarrhea has a creamy or pasty appearance, may contain mucus, and typically lasts up to 5 days. Blood is usually absent. Inflammation of mucosa is mild compared to CpC. At necropsy, the small intestine is flaccid, thin-walled and gas-filled with watery contents.